The Ghost of A.W. Phillips

The Fed and the pesky Phillips Curve

The Federal Reserve Act mandates that the Federal Reserve conduct monetary policy "so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates." – Monetary Policy Principles and Practice

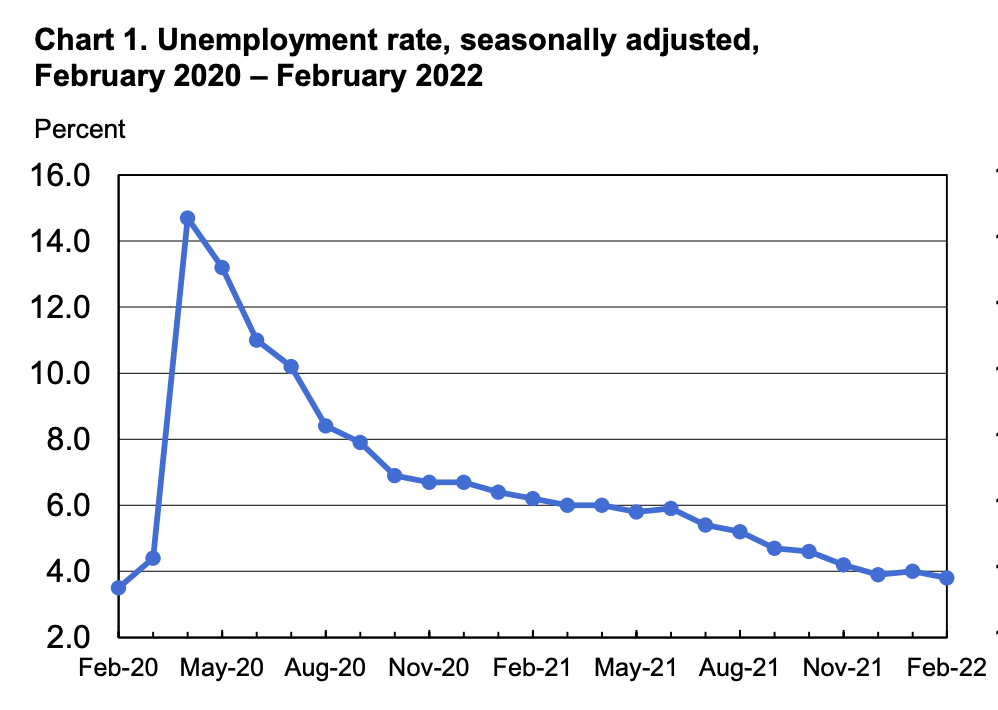

UC Berkeley's Jón Steinsson asks the obvious question about whether we'd be more aggressive in the face of the highest rate of inflation in the past 40 years coupled with an unemployment rate of 3.8% if we went back in time 3 years.

Remember, the Federal Reserve has a dual mandate to balance between employment an interest rates. Steinsson is wondering if unemployment is low (which it is when you compare to pre-pandemic levels), whether you'd expect a much more aggressive posture with respect to inflation.

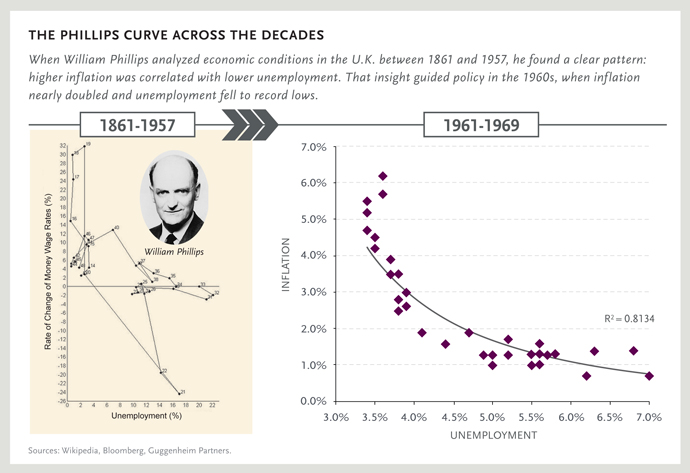

The relationship between unemployment and inflation was first explored by A. W. Phillips in 1958 in which he suggested an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation.

Phillips reasoned that when unemployment is high, workers are relatively easy to find and so wages hardly rise (if at all).

[I]n a year of rising business activity, with the demand for labour increasing and the percentage unemployment decreasing, employers will be bidding more vigorously for the services of labour than they would be in a year during which the average percentage unemployment was the same but the demand for labour was not increasing. Conversely in a year of falling business activity, with the demand for labour decreasing and the percentage unemployment increasing, employers will be less inclined to grant wage increases, and workers will be in a weaker position to press for them.

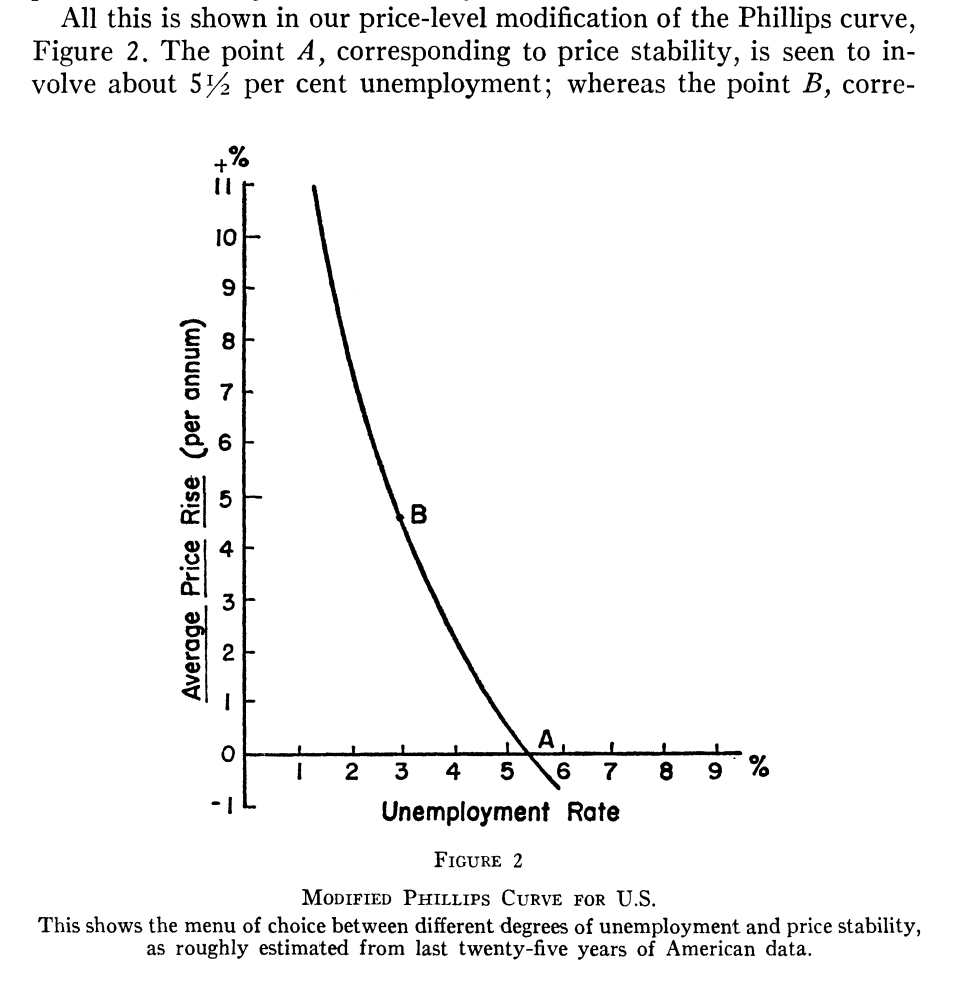

In 1960, Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow, writing in the American Economic Review, found a similar correlation between unemployment and inflation which they called the "Phillips curve".

As Greg Mankiw points out, most economists have come to believe there is a trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

Today, most economists believe there is a trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the sense that actions taken by a central bank push these variables in opposite directions. As a corollary, they also believe there must be a minimum level of unemployment that the economy can sustain without inflation rising too high. – Greg Mankiw (2019)

In a recent Washington Post op-ed , Larry Summers argues that the Fed has fanned the flames of inflation over the course of the past year operating with "an inappropriate and dangerous framework" and that it has "failed to internalize the magnitude of its errors".

He goes on to catalogue the actions taken over the course of the past year:

A year ago, the Fed thought inflation would be in the 2 percent range for the next year. Six months ago, it was expressing optimism that inflation was transitory. Two weeks ago, it was still buying mortgage-backed securities even as house prices had increased by more than 20 percent. No explanation has been offered for these rather momentous errors. – Larry Summers (March 2022)

Summers predicts that unless there are dramatic changes, the Fed has knowingly set the stage for a period where both unemployment and inflation will clock in over 5%:

Anything is possible, and wishful thinking can sometimes prove self-fulfilling. But I believe the Fed has not internalized the magnitude of its errors over the past year, is operating with an inappropriate and dangerous framework, and needs to take far stronger action to support price stability than appears likely. The Fed’s current policy trajectory is likely to lead to stagflation, with average unemployment and inflation both averaging over 5 percent over the next few years — and ultimately to a major recession. – Larry Summers (March 2022)

He argues that with the macroeconomic variables at play (higher energy prices, higher grain prices due to war in Ukraine, and COVID lockdowns in China), it's not unlikely that we see even higher inflation, thus increasing the likelihood of the deadly wage-price spiral:

We now face major new inflation pressures from higher energy prices, sharp run-ups in grain prices due to the Ukraine war, and potentially many more supply-chain interruptions as covid-19 forces lockdowns in China. It would not be surprising if these factors added three percentage points to inflation in 2022. And with price increases outstripping wage increases, a wage-price spiral is a major risk.

The reason why Summers mentions the wage-price spiral is related to both the Phillips Curve and the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU). The NAIRU, first proposed by Milton Friedman, is a natural rate of unemployment below which you would start to see inflation. The spiral is outlined below:

- Unemployment is low meaning workers are scarce. In order to attract workers, you have to pay them more.

- Higher pay can then be borne by business in one of two ways: 1) keep prices the same and accept lower margins or 2) raise prices and pass through the higher cost of labor.

- Case 1) is unlikely to happen (and no, that's not "corporate greed"). As such, prices rise and workers demand more money to make up for the fact that their purchasing power diminished with the price increases.

- Higher pay leads to greater price increases which causes workers to ask for more money.

And this is where we are at right now. The Fed now faces a question about which path to take:

- Do they raise interest rates to show that they are taking inflation seriously and risk rising unemployment?

- Or do they gradually dip their toe in the water and slowly increment interest rates at 25bps.

At least people aren't still arguing that inflation is transitory...